|

Producing Your Own Fanzine

In many fan clubs on both sides of the Atlantic there exists the fascinating occupation known as "running a fanzine".

Fictional and non-fictional, these fanzines or fanmags, call them what you will, contribute much to modern science-fiction literature. New ideas and the expression of new theories are the bread and butter of progress, and there is no reason why the bakers of this scientific dough should not be drawn from the ranks of countless thousands of enthusiastic fans.

Apart from its functional aspect, the fanzine offers the opportunity for self expression. There must be many science-fiction authors who, before taking the plunge and putting pen to paper, never dreamed of the latest literary talents that lurked, like an outsize B.E.M within them.

Why is it that many clubs do not produce even a news-sheet, let alone a fanzine? The answer in most cases is probably the question of finance. Club funds are not always what they should be, and even though a fanzine can be sold to help the club out of its financial doldrums, fans are not encouraged to action when confronted with expensive printing estimates and quotes.

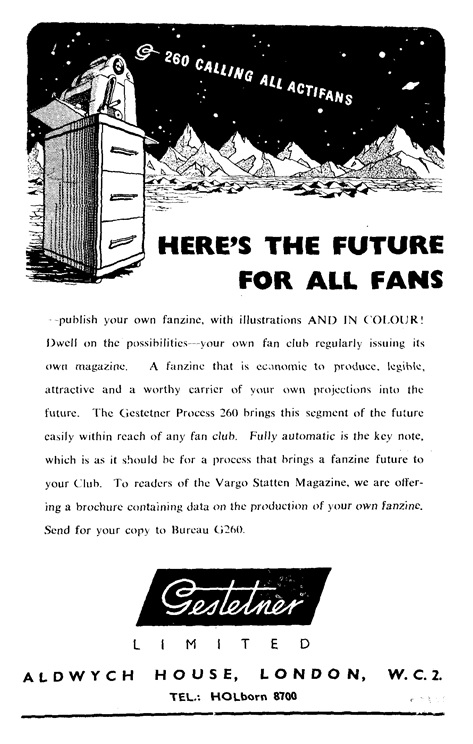

There is, however, an answer to this seemingly insoluble problem—the Gestetner process. The inventors and pioneers of this process, Messrs. Gestetner, Ltd., have made enormous progress in recent years, and their latest model—the 260—will transform any club into a self-contained fanzine production unit.

Many editors realise the importance of colour and illustration, two factors contributing to the bright and attractive appearance of their fanmag, but what can they do with price against them?

The answer again lies in the Gestetner Process, where coloured illustrative work is as simple, quick and inexpensive to prepare and run as black and white.

The most convenient size for a magazine typed on a standard elite typewriter is quarto 8 1/4" x 10 3/8". However, the foolscap sheet 8 1/4" x 13" can easily be folded and made into a four-page folder measuring 6 1/2"x 8 1/4". This is probably the most popular size amongst fan clubs.

Begin by making a "mock-up" or dummy magazine, with the correct number of sheets and folds required, and rule in pencil on each page the area to be filled by type matter and illustrations; this is known as the "type area" and should be the same throughout the magazine. Take care to get a balanced appearance on a two-page spread by the correct placing of the type areas on the pages. List your stories and mark off in the dummy the pages to be allocated to each. Always start a fresh right-hand page for a long or important story. Try to get variety by interspacing the longer stories with short announcements, reviews and other items of interest. If you are an artist you will have no difficulty in sketching into position a number of appropriate illustrations. They have a dual purpose—to attract attention to special stories and to avoid the monotony of pages of unrelieved type.

Even if you cannot draw, Gestetner have a wide range of stock illustrations which can be used to brighten your pages.

Finally, type out your subject matter, or "copy" to give it its correct name, and paste it into your dummy to exactly fit the type area, leaving the illustrations uncovered.

Your dummy should now show you how the finished magazine will look; careful checking should be carried out and all alterations should be made at this stage before cutting the stencils.

The editor of a fanzine can (and should) make extensive use of the photographic stencil. This is known as the Gesteprint process, after its inventor, David Gestetner. With these photographically prepared stencils, anything typed, typeset, written or drawn can be reproduced. In fact, there is no limit to the variety of open line illustrations which can be duplicated. Photographs with good contrasts of light and shade may also be reproduced as screened half-tone illustrations.

The Gestetner Model 260 is a robot as far as operating is concerned. Set the dials, turn the switch and it will run itself with every copy perfect—and there are no block or printing charges to worry about.

All editors and prospective publishers of fanmags would be well advised to see this Gestetner 260 in action. It opens the door to new worlds in fanzine production and is virtually the only process where production cost does not raise its formidable head.

|